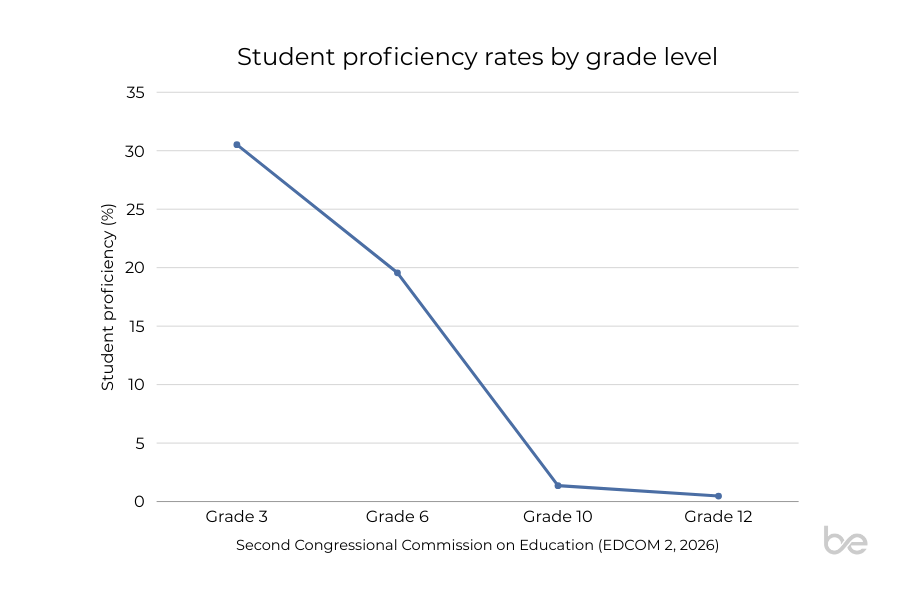

The 2026 national data on student proficiency in the Philippines has sparked renewed concern across the education sector. According to findings released by the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM 2), proficiency rates decline sharply as learners progress through the K–12 system—dropping from around 30 percent in Grade 3 to less than 1 percent by Grade 12. These figures are difficult to ignore, especially for educators who encounter learning gaps daily in their classrooms.

While statistics alone cannot capture the full complexity of teaching and learning, they offer an important opportunity for reflection. Rather than assigning blame, the data invites educators, institutions, and education technology builders to examine how learning is supported, assessed, and understood across different stages of schooling.

Rather than treating these results as a standalone report, this article looks at student proficiency data as a signal worth interpreting carefully. The goal is not to draw conclusions about effort or effectiveness, but to reflect on what these patterns suggest about learning and assessment as students progress through different grade levels—especially from the perspective of educators working in classrooms.

To do this, the discussion moves across several connected perspectives: what national proficiency results show, what student proficiency actually measures, how learning foundations develop over time, and how understanding becomes visible through different forms of classroom assessment. Taken together, these lenses help provide a more complete picture of how learning challenges emerge and persist across schooling years.

Interpreting proficiency data meaningfully requires a clear understanding of what the metric is designed to capture, and how it is commonly used in large-scale assessments.

Understanding What “Student Proficiency” Measures

Student proficiency is often treated as a single indicator of learning success, yet it represents a specific and limited view of student capability. In large-scale assessments, proficiency typically reflects a learner’s ability to meet predefined benchmarks in literacy, numeracy, or subject knowledge under standardized conditions. These benchmarks are useful for system-level monitoring, but they do not always align with how understanding appears in real classrooms.

Many educators observe that students can complete written tasks, pass exams, or advance grade levels while still struggling to explain concepts clearly or apply knowledge in unfamiliar contexts. As academic content becomes more abstract in later grades, this gap between surface performance and deep understanding becomes harder to detect through conventional assessment formats alone.

The EDCOM 2 findings do not suggest that learning suddenly collapses in senior high school. Instead, they highlight how early gaps in comprehension and expression can persist and compound over time, especially when assessment tools are limited in their ability to surface how students think.

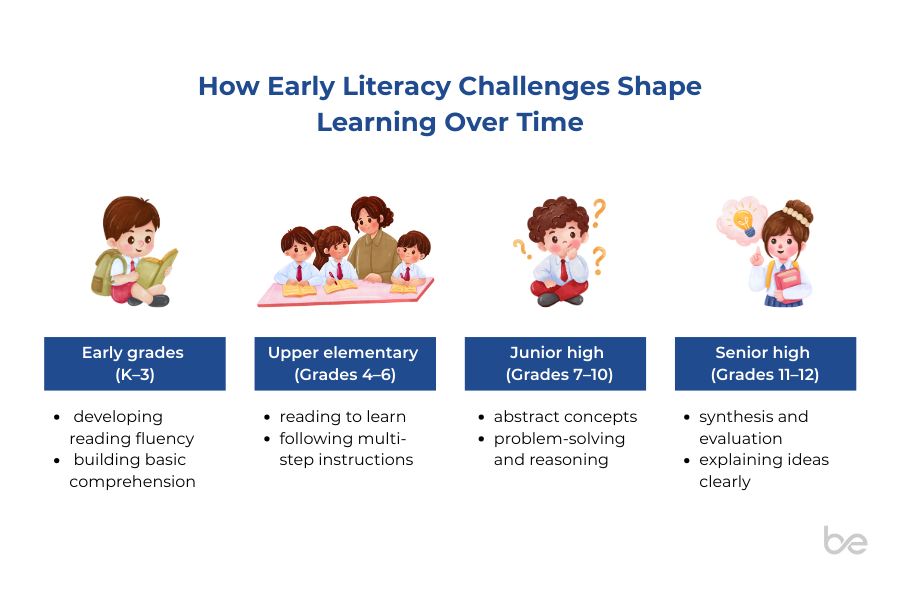

Looking more closely at how proficiency is measured also draws attention to when learning gaps tend to emerge, and how early foundations influence what students are expected to demonstrate in later stages of schooling.

Foundational Learning and the Compounding Effect of Early Gaps

One of the most significant insights from the EDCOM 2 report is the role of early literacy and foundational skills. By the end of Grade 3, a substantial proportion of learners are already struggling to read at grade level. This early difficulty creates barriers to learning in later years, when students are expected to engage with more complex texts, ideas, and problem-solving tasks.

Educators are often keenly aware of this reality. Within the constraints of large class sizes, limited instructional time, and curriculum requirements, teachers frequently rely on informal checks for understanding—asking students to explain answers, discuss ideas, or articulate reasoning. These practices offer valuable insight, yet they are difficult to scale or document consistently across classrooms and schools.

At a system level, this raises an important question: how can assessments better support educators in identifying learning needs early, while also respecting the professional judgment that teachers bring to their classrooms?

As learning demands become more complex across grade levels, the ways students demonstrate understanding also evolve, highlighting the importance of recognizing multiple forms of expression in classroom assessment.

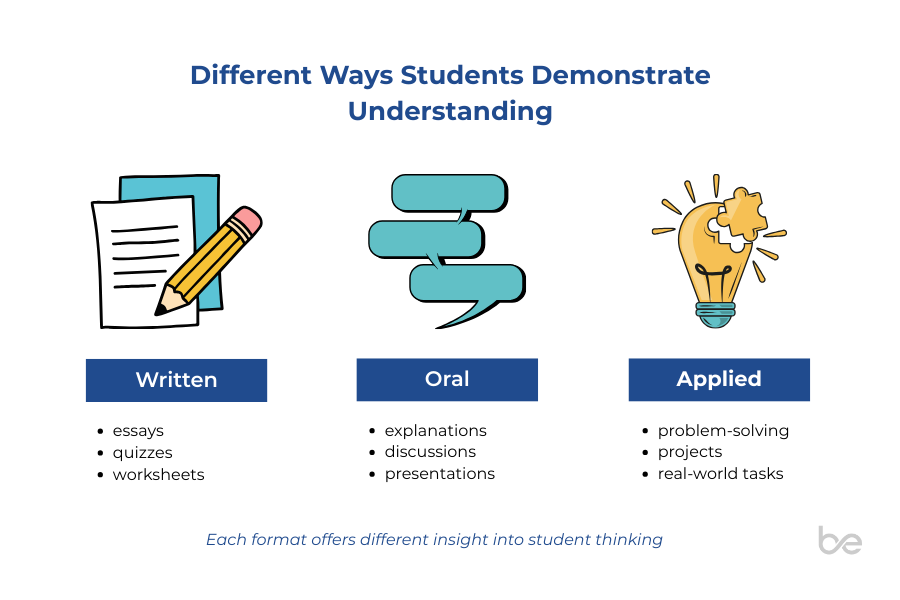

Assessment as Visibility Into Learning

As students grow older, assessment plays an increasingly important role in shaping academic pathways and opportunities. Written tests and standardized exams provide efficiency and comparability, yet they often prioritize final answers over learning processes. For complex subjects, understanding is demonstrated through explanation, reasoning, and the ability to connect ideas—skills that are not always visible in traditional assessment formats.

Viewing assessment as a source of insight rather than evaluation alone can shift how learning data is interpreted. When educators gain clearer visibility into how students reason, they are better equipped to support learning, adjust instruction, and provide meaningful feedback. This perspective aligns with long-standing pedagogical practices that value dialogue, reflection, and formative assessment.

The national student proficiency data reinforces the importance of making understanding visible throughout a learner’s journey, particularly as content demands increase.

Responsible AI, Policy Direction, and Project AGAP.AI

Against this backdrop, recent policy developments offer an important signal. In January 2026, the Philippine government launched Project AGAP.AI, a national initiative aimed at strengthening AI literacy in basic education. The program emphasizes responsible, ethical, and practical engagement with artificial intelligence, targeting students, teachers, and school leaders alike.

Project AGAP.AI reflects a growing recognition that AI will play a role in education, and that guidance is necessary to ensure its use supports learning rather than undermines it. Importantly, the initiative highlights teacher agency, data privacy, and critical thinking as core principles.

Within this policy context, discussions about assessment become even more relevant. Responsible AI applications in education have the potential to support educators by providing additional perspectives on student understanding, particularly when designed to complement—not replace—professional judgment. Used thoughtfully, such tools can help surface patterns in learning while keeping educators at the center of decision-making.

A Shared Responsibility Moving Forward

Viewed together, the proficiency data, learning foundations, and assessment practices point to a shared challenge: understanding student learning requires more than a single measure or moment in time. Proficiency results offer valuable signals, but they gain meaning when considered alongside how students build knowledge over time and how their understanding is observed and supported in classrooms.

The decline in student proficiency documented by EDCOM 2 is a system-wide concern that calls for collective reflection. Educators continue to carry the responsibility of supporting learners within complex realities. Institutions shape the conditions under which teaching and assessment occur. Policymakers set priorities and provide direction. Technology builders must approach education with care, humility, and responsibility.

Rather than offering quick solutions, the current moment invites deeper attention to how learning is observed, supported, and understood over time. Student proficiency data, when read thoughtfully, can guide more informed conversations about assessment practices, early intervention, and the role of emerging technologies in education.

As the Philippines moves forward with initiatives like Project AGAP.AI, maintaining a focus on learning integrity and educator empowerment will be essential. The challenge ahead lies in translating data into insight—and insight into meaningful support for both teachers and learners.

References

Second Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM 2). (2026). Student proficiency rates plunge from 30% in Grade 3 to 0.47% in Grade 12. https://edcom2.gov.ph/student-proficiency-rates-plunge-from-30-in-grade-3-to-0-47-in-grade-12/

Philippine Information Agency. (2026). Marcos Jr. launches AI literacy program for basic education students. https://pia.gov.ph/news/marcos-jr-launches-ai-literacy-program-for-basic-education-students/

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). PISA 2018 results (Volume I): What students know and can do. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/

Department of Education (Philippines). (2023). National learning recovery program framework. https://www.deped.gov.ph/